For most English language readers, the need to be a polyglot is over: so much is being translated into the English language from just this one language. But vice versa, there is little or no traffic. For serious readers of English literature, particularly if they come from the continent, the term has come to mean literature translated from other world languages into English. On their reading lists, one will find few English authors. Forgive one’s colonial masters. This feeling is further strengthened when one comes to realise the strange alchemy of the translation process. Whole cultures and whole worlds are translated when a language is translated from its ‘solo’ to other scripts. Non-English writers practicing in worlds are so alien to each other that they stand out in translation from the reality of the language translated from. Art in translation is the rule not the rarity. But sometimes it happens otherwise. Maybe it is the words themselves which matter each time, and each word finds its own soul, its own setting, its own colour. Translators from Russian and South American literature seem to go belong to the latter category. Although, there is little in common between these two literatures, except for the passion with which the writer gives expression to his statement in both, that statement is profound in the former and manifests itself openly with great force in the latter. Gabriel Garcia Marquez is perhaps unique among those South American writers who have introduced us to the term and the meaning of magical realism. He is known to us mainly through his novels Love in the Time of Cholera, and the Chronicle of a Death Foretold (this last becomes faded, alas, through frequent misquotation). I recall as a young man who, after reading One Hundred Years of Solitude, gave away all his belongings and sets out in search of this…. Another young man after reading the same novel gave up all ambitions and wandered aimlessly for months. They are both real. … No one now feels the need to search anything. If nothing they are a tribute to the writer who, through his narrative, exercises such a compelling influence on his readers. It was this narrative magic which prompted the Czech writer Milan Kundera to say that it is absurd to speak of the demise of the novel when Marquez has just published One Hundred Years of Solitude. A selection from Marquez’s novels, novellas and short stories has been published by “Aaj Ki Kitaben” from Karachi. The book is edited by Ajmal Kamal and includes in it new translations by Zahida Hina from Panama, Abid Saeed, Syed Naqsh Bilqifi, Asif Farrukhi, Ata Siddiqui, and Zeenat Hissam. All of these have been made from the English translations of Marquez’s works, e.g., the novella, Chronicle of a Death Foretold has been translated by Abul Hayee]. Syed Parvez Hasani has translated No One Writes to the Colonel. One short story and several pieces from One Hundred Years of Solitude are translated by Zeenat Hissam and the second chapter of Love in the Time of Cholera is by Ata Siddiqui. The Incredible and Sad Tale of Innocent Erendira and Her Heartless Grandmother has been translated by Zahida Hina. Two short stories, one shorter, shorter or inner-side, for this story (But let me not review Marquez, let me not my place… where was I? Yes! yes.) are from the pen of the writer. The book begins with a personal introductory essay about Garcia Marquez from writer’s point of view. It is based on Marquez’s interview with Plinio Apuleyo Mendoza. It traces Marquez’s childhood, his adolescence, his development as a writer and his transition to fiction. It tells of the… extreme poverty which descended on Marquez when a Colombian dictator stopped the publication of the column which he wrote daily as well as the Paris correspondent. Then there was the day when the writer finally arrived as a ‘man of letters’. There was a point while he was writing One Hundred Years of Solitude, says Marquez, when his wife asked him what would happen if the book was boring. It was an act which he could not bring himself to do. After he had finally finished the book he had no idea what kind of book he had actually written. She was shaking. One look at Marquez’s face told his wife what must have had happened. When she finished reading the book she (Marquez) went to his bed and broke into sobs. Telling his friend Mendoza of the still unwritten One Hundred Years of Solitude, Marquez had said, “If I don’t write it I am a failure,” and, “If I put a gun to my temple and blow my brains out”. Marquez went on to receive the 1982 Nobel Prize for Literature, but the alienation which had prompted him to become what he became, continued to dog him. His acceptance speech… alienation is an issue which faces everyone. Everyone reacts to it in his or her own particular manner [which he calls] ‘denial’. Marquez strikes the nerve at the core of so many writers’ works, although some writers are innocent of any conscious attempt at ‘denying’ it. In the text of his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, Marquez elaborates why magical realism is not mere whimsy but grows directly from the Latin American realities. For them it is not a surrealist portraiture of life, but realism. With the Latin American reality reflected in his successive tables of fantastic population and suicidal attitudes which resulted from it, it is a writer’s attempt to exercise the magical realism by his craft. He asks the West not just to look and listen to his statements but to listen and look and help create the conditions for enabling the normal individual to live in South America. Marquez mentions The Autumn of the Patriarch as his most important work from the literary point of view. A book which, he claims, would save him from oblivion. He calls the use of language at a different language from his other works as one reason for this claim. He also confesses of his astonishment at Marquez’s lack of concern that so much of this book has been translated for this selection. Apart from the literary worth of his novels The Chronicle of a Death Foretold, which many critique as the best ever achievement; better than Nobody Writes to the Colonel which he rewrote nine times before he got published, and better still, his early writing The Chronicle he exercised absolute command over his craft and managed to mould the narrative element to his heart’s desire. Like every self-respecting writer Marquez slights critics and their attempts at dissecting his writing or laddering-ratings. Before the book closes, we read three essays. The first two examine Marquez’s work from the perspective of world literature and Latin American writings. The third essay is compiled from Marquez’s interview with Colombian novelist and his friend Plinio Apuleyo Mendoza. In this interview he speaks about himself, his art and the influences it received, including his literary and intellectual convictions, which are central to his life and work. An appendix is also given at the end which is a chronological list of his life’s in the backdrop of events in Latin America. The translations in this collection are flawless and refreshingly clear. Only people with their own individual styles are accomplished writers. The never-ending magic of these stories would haunt the reader many days after he puts the book down. Without a doubt this book is a representative collection of Marquez’s work, and, in its own right, a landmark publication in Urdu literature. To be able to write in a language, one needs a certain command of life. To be able to use that language to build on. Pakistan’s history with its more than fair share of the conditions and the commands in our local languages provide us with a great treasure trove for our writers to capitalise on. The sooner our writers realise that their destiny lies not in simply intriguing the West with interesting fare, but of maintaining an outward looking approach while keeping their feet on the ground, the better it will be for them. More than ever, there is a need for foreign contemporary literature to be translated from the source. It is good that this task is not being done in its. Urdu stands only to gain from such an endeavour being a relatively new language and providing a written counterpart equal to it. Translators deserve full credit for catering to this need and introducing non-subcontinental names and ideas. And perhaps, even when Urdu publications are fast becoming quality-unconscious, both in form and content.

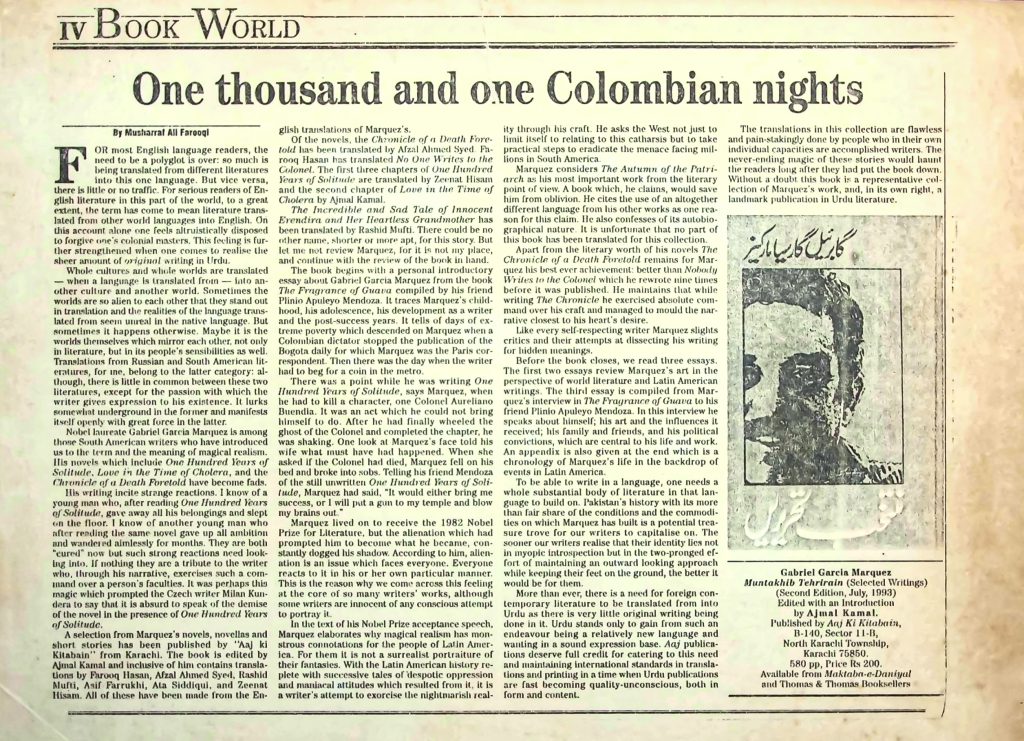

(05) Muntakhab Tehreerien Review