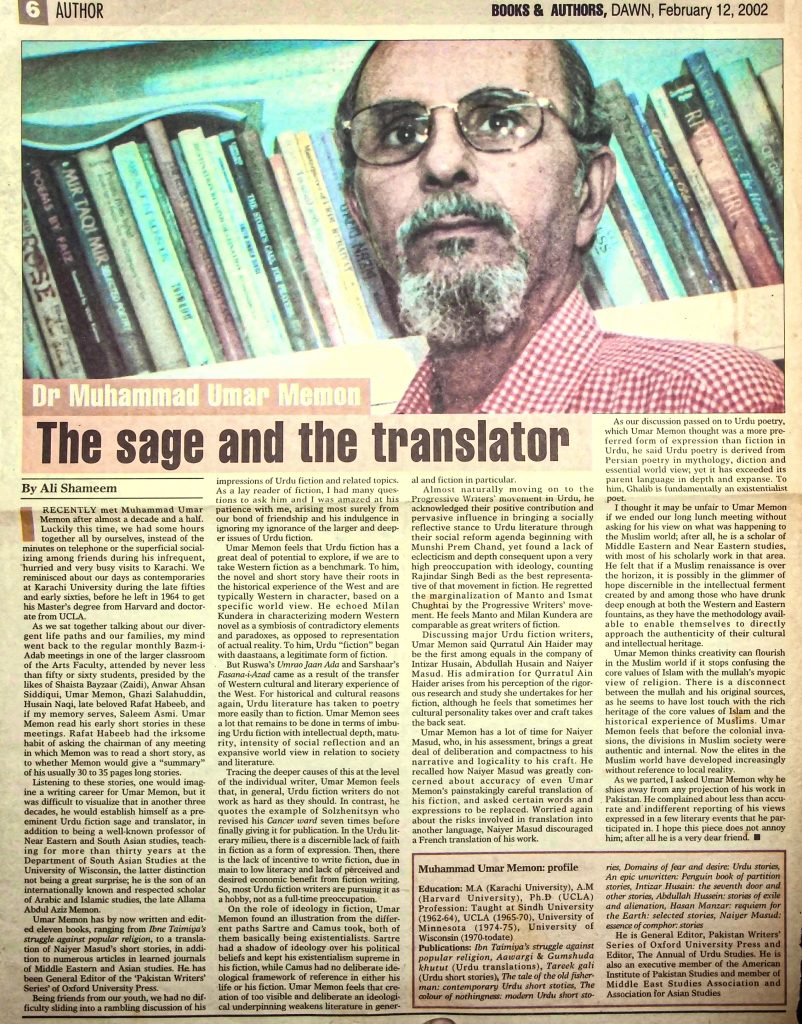

Dr Muhammad Umar Memon – The Sage and the translator

Ali Shameem

RECENTLY, met Muhammad Umar Memon after almost a decade and a half. We first met each other way back in 1965 together all by ourselves, instead of the mundane introduction by a common friend. We hit it off together as young friends during his infrequent, hurried and brief visits to his home town, Karachi. We talked about literature, art and culture, the life at Karachi University during the late fifties and early sixties, about his Ph.D. from UCLA, his master’s degree from Harvard and doctorate from Cairo. As we sat together talking about our divergent views on art and letters, his mind went back to the regular monthly Bazm-i-Shaheen gatherings at S.M. Law College, or those of the Arts Faculty, attended by never less than 500. He particularly remembered the papers presented by Josh Malihabadi, Shaukat Siddiqui, Umar Memon, Ghazi Salahuddin, and Akhtar Husain. He asked if these meetings, or if my memory serves, Saleem Asmi, Umar Memon, and my good self, continue those meetings. Rafat Habeeb had the irksome habit of attending these meetings uninvited in which Memon was to read a short story, as he used to. Memon explained: “I normally write 30 to 35 pages long stories.” I could see from his smile he could imagine the presence of just five to six people. It is not difficult to visualize that in another three decades, there would hardly be any reviewer, eminent Urdu fiction sage and translator, in addition to being a senior professor in the Near Eastern and South Asian studies, teaching Urdu, Arabic, and Persian, in the Department of South Asian Studies at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. Memon not being a great surprise, he is the son of an eminent academician and scholar of repute of Arabic and Islamic studies, the late Allama Abdul Aziz Memon. Prof Memon has so far written and edited eleven books, ranging from Ilm-i Taaleem (a major reference work) to Intizar Husain’s translation of Naiyer Masud’s short stories, in addition to writing more than forty scholarly articles of Middle Eastern and Asian studies. He has just finished editing a volume, ‘Urdu Stories Series’ of Oxford University Press. As we continued to talk, we had no difficulty sliding into a rambling discussion of his impressions of Urdu fiction and related topics. He very kindly allowed me to raise objections to ask him and I was amazed at his profound insight. Memon feels strongly that our bond of friendship and his indulgence in writing and translating fiction has weathered the vagaries of time and circumstance. He feels that Urdu fiction has a rather slim body as compared to the whole, let’s say, Western fiction as a benchmark. To him, the novel form in particular is derived from the historical experience of the West and are basically informed by a middle class view of a specific world view. He echoed Milan Kundera when he talked about the novel as a synthesis of contradictory elements and not a simple narration, nor a chunk of actuality. To him, Urdu ‘fiction’ began with Hasan Askari, Mumtaz Shirin, Intizar Husain, Enver Sajjad, Naiyer Masud, and so on. He mentioned Hasan Askari’s Jhalkian, Janoon Latif and Intizar Husain’s Basti. For him, the question of identity is central, as it is in the West. For historical and cultural reasons alone, Urdu fiction has ‘always’ been more easily than to fiction. Umar Memon sees no ‘real’ tradition. He has been reading and editing Urdu fiction with intellectual depth, maturity and stylistic grace. He feels that the expansive world view in relation to society is essential. Tracing the deeper causes of this at the level of the publisher, he saw little difference between reviewing a draft of any serious fiction work as hard as they should. In contrast, he quoted John Updike whose publisher had revised his Centaur seven times before it finally went to the press. Given the contemporary milieu, there is a discernible lack of faith in fiction as a ‘high’ art form. More distressing is the lack of incentive to write fiction, due in part to its minimal financial reward and the desired economic benefit from fiction writing. He agrees: “Serious fiction writing remains a hobby, at least it is true in our society.” As the role of ideology in fiction, Umar Memon reviewed the intellectual and different paths Sartre and Camus took, both of whom started writing after World War II. Sartre had a shadow of ideology over his political beliefs, but it did not impinge too heavily on his fiction, while Camus had no deliberate ideology and there are no signs of it anywhere in his life or his fiction. Umar Memon feels that creative fiction cannot be “written” to a philosophical underpinning western literature in general and fiction in particular. Before closing and moving on to the Progressive Writers’ movement in Urdu, he mentioned that the PWA in Urdu did have its pervasive influence in bringing a socialist message as it was in the interest of to see their social reform agenda beginning with its first manifesto in London in 1935. A good number of Urdu fiction writers felt a high preoccupation with ideology, counting perhaps more heavily than its “representational” or that of movement in fiction. He regretted that Qurratulain Haider has not been fully explored. He thought that the Progressive Writers’ movement has had some fine short stories, “but not many comparable as great writers of fiction.” Of the contemporary Urdu fiction writers, Umar Memon said Qurratulain Haider may be cited as an example of an attempt at integrating cultural synthesis with Intizar Husain. His admiration for Qurratulain Haider has been very consistent. He feels that the research and study she undertakes for her novels, the range of her intellectual and cultural personality takes over and craft takes the back seat. Umar Memon has a lot of time for Naiyer Masud. He has translated his fiction “after a deal of deliberation and comparisons to his advantage.” As a side remark, Umar Memon recalled how Naiyer Masud was greatly impressed about accuracy of even Umar Memon’s “casual reading.” He had read most of his fiction and asked certain words and their meanings, and Naiyer Masud talked about the risks involved in translation into English. He feels that there should have been a French translation of his work. As our discussion passed on to Urdu poetry, which Umar Memon thought was a more private, rather than a narrative, art form as is fiction. He found a greater emotional pull in Persian poetry in mythology, diction and form, and there is more in the grandmother/parent language in depth and expanse. To him, Hafiz is a more enduring and greater poet. I thought it may be unfair to Umar Memon if we ended our long lunch meeting without talking about Islam and its relationship to the Muslim world after 9/11. He saw “little change” in the Middle Eastern and Near Eastern studies, programs in the “leading” universities in the US. He felt that if a Muslim renaissance is without Islam, it is not possible. He feels “it is desirable in the intellectual ferment not to lose touch with Islam.” He feels there is a deep enough at both the Western and Eastern seats of learning. He also felt Muslims must be able to enable themselves to directly understand and appreciate the Quranic, Arabic and intellectual heritage. Umar Memon thinks creativity can flourish in the Muslim world if a compatibility of the core values of Islam with the Mullah’s myopic view of ‘reality’, that is, a clear distinction between the mullah and his original sources, is re-established, along with the heritage, the rich heritage of the core values of Islam and the Quran and Sunnah remain ‘constant’. Umar Memon feels that before the colonial invasion, the educational system of the East was authentic and internal. Now the cities in the Muslim world seem alien, look disturbingly Western, rootless and parasitic. As we parted, I asked Umar Memon why he had chosen self-exile and never returned to Pakistan. He complained about less than academic freedom in the universities. He also expressed in a few literary events that he particularly cherished. He often visits Karachi to see his son, all in all, he is a very dear friend. Muhammad Umar Memon: profile Education: M.A (Karachi University), A.M (Harvard University), Ph.D. (UCLA). Profession: Taught at Sindh University (1962-63), UCLA (1964-65), University of Minnesota (1974-75), University of Wisconsin (1970-present). Publications: Ilm Taalim (a struggle against non-functional education), Izhar-o-shuur (Urdu translations), Farrokh goft (contemporary Persian fiction), Doosri manzil (contemporary Urdu short stories), The contemporary Urdu short story, Intizar Husain’s Basti, Intizar Husain: the seventh door and other stories, Intizar Husain: stories of partition and alienation, Hasan Manzar: requisite for a vision of the ultimate, Naiyer Masud: the essence of camphor stories. Other publications: Pakistan Writers’ Series of Oxford University Press and others, Urdu editor, Annual of Urdu Studies, also an executive member of the American Institute of Pakistan Studies, vice-president, Middle East Studies Association and Association for Asian Studies.