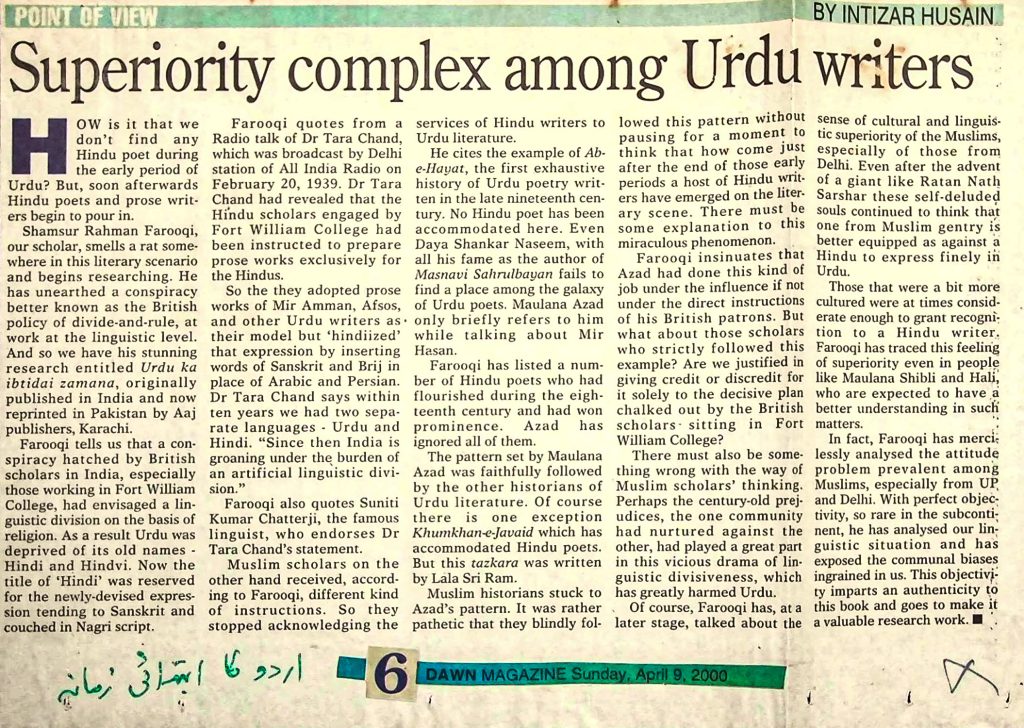

POINT OF VIEW

BY INTIZAR HUSAIN

Superiority complex among Urdu writers

H OW is it that we don’t find any Hindu poet during the early period of Urdu? But, soon afterwards Hindu poets and prose writ ers begin to pour in.

Shamsur Rahman Farooqi, our scholar, smells a rat some where in this literary scenario and begins researching. He has unearthed a conspiracy better known as the British policy of divide-and-rule, at work at the linguistic level. And so we have his stunning research entitled Urdu ka ibtidai zamana, originally published in India and now reprinted in Pakistan by Aaj publishers, Karachi.

Farooqi tells us that a con-spiracy hatched by British scholars in India, especially those working in Fort William College, had envisaged a lin-guistic division on the basis of religion. As a result Urdu was deprived of its old names Hindi and Hindvi. Now the title of ‘Hindi’ was reserved for the newly-devised expres sion tending to Sanskrit and couched in Nagri script.

Farooqi quotes from a Radio talk of Dr Tara Chand, which was broadcast by Delhi station of All India Radio on February 20, 1939. Dr Tara Chand had revealed that the Hindu scholars engaged by Fort William College had been instructed to prepare prose works exclusively for the Hindus.

So the they adopted prose works of Mir Amman, Afsos, and other Urdu writers as their model but ‘hindiized’ that expression by inserting words of Sanskrit and Brij in place of Arabic and Persian. Dr Tara Chand says within ten years we had two sepa rate languages Urdu and Hindi. “Since then India is groaning under the burden of an artificial linguistic divi sion.”

Farooqi also quotes Suniti Kumar Chatterji, the famous linguist, who endorses Dr Tara Chand’s statement.

Muslim scholars on the other hand received, accord ing to Farooqi, different kind of instructions. So they stopped acknowledging the

services of Hindu writers to Urdu literature. He cites the example of Ab

e-Hayat, the first exhaustive history of Urdu poetry writ ten in the late nineteenth cen tury. No Hindu poet has been accommodated here. Even Daya Shankar Naseem, with all his fame as the author of Masnavi Sahrulbayan fails to find a place among the galaxy of Urdu poets. Maulana Azad only briefly refers to him while talking about Mir Hasan.

Farooqi has listed a num ber of Hindu poets who had flourished during the eigh teenth century and had won prominence. Azad has ignored all of them.

The pattern set by Maulana Azad was faithfully followed by the other historians of Urdu literature. Of course there is one exception Khumkhan-e-Javaid which has accommodated Hindu poets. But this tazkara was written by Lala Sri Ram.

Muslim historians stuck to Azad’s pattern. It was rather pathetic that they blindly fol

lowed this pattern without pausing for a moment to think that how come just after the end of those early periods a host of Hindu writ ers have emerged on the liter ary scene. There must be some explanation to this miraculous phenomenon.

Farooqi insinuates that Azad had done this kind of job under the influence if not under the direct instructions of his British patrons. But what about those scholars who strictly followed this example? Are we justified in giving credit or discredit for it solely to the decisive plan chalked out by the British scholars sitting in Fort William College?

There must also be some thing wrong with the way of Muslim scholars’ thinking. Perhaps the century-old prej udices, the one community had nurtured against the other, had played a great part in this vicious drama of lin guistic divisiveness, which

has greatly harmed Urdu. Of course, Farooqi has, at a later stage, talked about the

sense of cultural and linguis-tic superiority of the Muslims, especially of those from Delhi. Even after the advent of a giant like Ratan Nath Sarshar these self-deluded souls continued to think that one from Muslim gentry is better equipped as against a Hindu to express finely in Urdu.

tion to a Hindu writer. Those that were a bit more cultured were at times consid-erate enough to grant recogni Farooqi has traced this feeling of superiority even in people like Maulana Shibli and Hali, who are expected to have a better understanding in such matters.

In fact, Farooqi has merci lessly analysed the attitude problem prevalent among Muslims, especially from UP, and Delhi. With perfect objec tivity, so rare in the subconti nent, he has analysed our lin guistic situation and has exposed the communal biases ingrained in us. This objectivi ty imparts an authenticity to this book and goes to make it a valuable research work.

اردو کا ابتدائی زمانہ

6

DAWN MAGAZINE Sunday, April 9, 2000

image72