BOOKS & AUTHORS, DAWN, January 29, 2002

WEBSITE REVIEW

By Ajmal Kamal

66 WELCOME to the Garden of Forking Paths, one of the most intriguing areas of the Labyrinth of Allexamina. Here you will find access to

the 1920’s in Buenos Aires, nobody thought of literature in terms of failure or suc-cess,” Borges says in one of his interviews published in the New York Times on April 6, 1971, and available on the web at the NY Times site “You might publish an edi tion of 300 copies and these you gave away to your friends.

The days of scarcity, it seems, are now over, thanks to the Internet. And, one finds it appropriate that Borges’ world is approached through the new, everyday version of one of his many

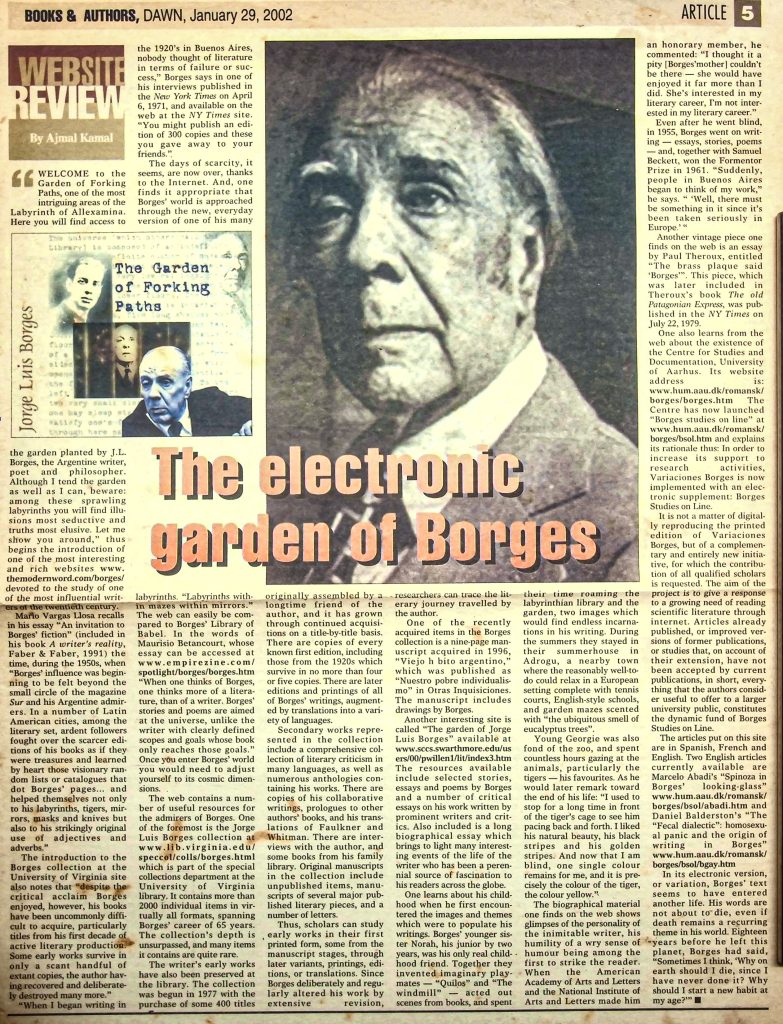

The Garden of Forking Paths

Jorge Luis Borges

Lyre

the garden planted by J.L… Borges, the Argentine writer, poet and philosopher. Although I tend the garden.

well as I can, beware among these sprawling labyrinths you will find illu sions most seductive and truths most elusive. Let me begins the introduction of one of the most interesting and rich websites www. themodernword.com/borges/devoted to the study of one of the most influential writ s of the twenneth century

Mario Vargas Llosa recalls in his essay “An invitation to Borges’ fiction” (included in his book A writer’s reality, Faber & Faber, 1991) the time, during the 1950s, when “Borges” influence was begin ning to be felt beyond the small circle of the magazine Sur and his Argentine admir ers. In a number of Latin American cities, among the literary set, ardent followers fought over the scarcer edi tions of his books as if they were treasures and learned by heart those visionary ran dom lists or catalogues that dot Borges pages… and helped themselves not only to his labyrinths, tigers, mir rors, masks and knives but also to his strikingly original use of adjectives and adverbs.”

The introduction to the Borges collection at the University of Virginia site also notes that “despite the critical acclaim Borges enjoyed, however, his books have been uncommonly diffi-cult to acquire, particularly titles from from his first decade of active literary production Some early works survive only a scant handful of extant copies, the author hav ing recovered and deliberate

ly destroyed many more.” “When I began writing in

labyrinths. “Labyrinths with in mares within mirrors.” The web can easily be com pared to Borges Library of Babel. In the words of Maurisio Betancourt, whose essay can be accessed at www.empirezine.com/es.htm spotlight/borges/borges.htm “When one thinks of Borges, one thinks more of a litera ture, than of a writer. Borges stories and poems are aimed at the universe, unlike the writer with clearly defined. scopes and goals whose book only reaches those goals.” Once you enter Borges’ world d to adjust you would need to yourself to cosmic dimen sions.

The web contains a num ber ber of of useful resources for the admirers of Borges. One of the foremost is the Jorge Luis Borges collection at www.lib.virginia.edu/speccal/colls/borges.html which is part of the special collections department at the University of Virginia library. It contains more than 2000 individual items in vir tually all formats, spanning Borges’ career of 65 years. The collection’s depth is unsurpassed, and many items

it contains are quite rare. The writer’s early works have also been preserved at the library. The c The collection was begun in 1977 with the purchase of some 400 titles

The electronic garden of Borges

originally assembled by a longtime friend of the author, and it has grown through continued acquisi tions on a title-by-title basis. There are copies of every known first edition, including those from the 1920s which survive survive in in no no more than four or five copies. There are later editions and printings of all of Borges writings, augment ed by translations into a vari ety of 1 of languages.

Secondary works repre sented in the collection include a comprehensive col lection of literary criticism in many languages, as well as numerous anthologies con taining his works. There are copies of his collaborative writings, prologues to authors’ books, and his trans prologues to other lations of Faulkner and Whitman. There are inter views with the author, and some books from his family library. Original manuscripts in the collection include unpublished items, manu scripts of several major pub-lished literary pieces, and a

number of letters. Thus, scholars can study early works in their first printed form, some from the manuscript stages, through later variants, printings, edi tions, or translations. Since Borges deliberately and regu larly altered his work by extensive revision,

researchers can trace the lit erary journey travelled by the author.

One of the recently acquired items in the Borges collection is a nine-page man uscript acquired in 1996, “Viejo h bito argentino,” which was published as “Nuestro pobre individualis mo in Otras Inquisiciones. The manuscript includes drawings by Borges.

Another interesting site is called “The garden of Jorge Luis Borges” available at www.sccs.swarthmore.edu/us ers/00/pwillen1/lit/index3.htm The resources available include selected stories, essays and poems by Borges and a number of critical essays on his work written by prominent writers and crit ics. Also included is a long biographical essay which brings to light many interest ing events of the life of the writer who has been a peren nial source of fascination to his readers across the globe.

One learns about his child hood when he first encoun-tered the images and themes which were to populate his writings. Borges younger sis ter Norah, his junior by two years, was his only real child hood friend. Together they invented imaginary play mates “Quilns” and “The windmill acted out scenes from books, and spent

they stayed in their time roaming the labyrinthian library and the garden, two images which would find endless incarna tions in his writing. During the summers they stayed in their summerhouse in Adrogu, a nearby town where the reasonably well-to-do could relax in a European setting complete with tennis courts, English-style schools, and garden mazes scented with “the ubiquitous smell of eucalyptus trees”.

Young Georgie was also fond of the zoo, and spent countless hours gazing at the animals, particularly the tigers-his favourites. As he would later remark toward the end of his life: “I used to stop for a long time in front of the tiger’s cage to see him pacing back and forth. I liked his natural beauty, his black stripes and his golden stripes. And now that I am blind, one single ngle colour remains for me, and it is pre-cisely the colour of the tiger, the colour yellow.”

The biographical material one finds on the web shows glimpses of the personality of the inimitable writer, his humility of a wry sense of the humour being among the first to strike the reader. When the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the National Institute of Arts and Letters made him

ARTICLE

5

an honorary member, he commented: “I thought it a pity sity [Borges mother] couldn’t be there she would have enjoyed it far more than 1 did. She’s interested in my literary career, I’m not inter-ested in my literary career.”

Even after he went blind, in 1955, Borges went on writ ing essays, stories, poems and, together with Samuel Beckett, won the Formentor Prize in 1961. “Suddenly, people in Buenos Aires began to think of my work,” he says. “Well, there must be something in it since it’s been taken seriously in Europe”

Another vintage piece one finds on the web is an essay by Paul Theroux, entitled “The brass plaque said “Borges”. This piece, which was later included in Theroux’s book The old Patagonian Express, was pub lished in the NY Times on July 22, 1979.

One also learns from the web about the existence of the Centre for Studies and Documentation, University of Aarhus. Its website address is:

www.hum.aau.dk/romansk/borges/borges.htm Th Centre has now launched “Borges studies on line” at www.hum.nau.dk/romansk/borges/hsol.htm and explains. its rationale thus: In order to increase support to research activities, Variaciones Borges is now implemented with an elec tronic supplement: Borges Studies on Line.

It is not a matter of digital-ly reproducing the printed edition of Variaciones Borges, but of a complemen tary and entirely new initia tive, for which the contribu tion of all qualified scholars is requested. The aim of the project is to give a response to a growing need of reading scientific literature through internet. Articles already published, or improved ver-sions of former publications, or studies that, on account of their extension, have not been accepted by current publications, in fons, in short, every thing that the authors consid er useful to offer to a larger university public, constitutes the dynamic fund of Borges. Studies on Line.

The articles put on this site are in Spanish, French and English. Two English articles currently available are Marcelo Abadi’s “Spinoza in Borges looking glass” www.hum.aau.dk/romansk/borges/bsol/abadi.htm and Daniel Balderston’s “The “Fecal dialectic”: homosexu al panic and the origin of writing in Borges” www.hum.aau.dk/romansk/borges/bsol/bgay.htm

In its electronic version, or variation, Borges’ text seems to have entered another life. His words are not about to die, even if death remains a recurring theme in his world. Eighteen years before he left this planet, Borges had said, planet, Bor “Sometimes I think, “Why on earth should I die, since have never done it? Why should I start a new habit at my age?

image75